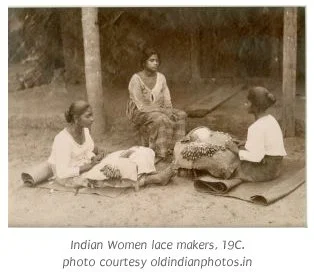

Lace Makers

India has always been a place of tremendous creative expression, whether articulated through color, cuisine, music, poetry, or fine arts - even through the delicate and intricate patterns of henna (mehndi) application. English lacemaking was a new art introduced by missionary Martha Mault in 1821. Her goal in teaching that art was to provide income to young, lower-caste women who had no other means to lift themselves and their families out of poverty. According to Indian author Joy Gnanadason's book, A Forgotten History, Mault also taught this craft to the slave girls to give them the means to buy back their freedom. She lived James 2:16: "If one of you says to them, 'Go in peace; keep warm and well fed,' but does nothing about their physical needs, what good is it?"

Martha Mault was from Honiton, an area in East Devon. The Allhallows Museum of Lace in Devon recounts that lace making, which had probably spread from Italy throughout Europe, has been recorded in the area from the 17th century, perhaps earlier. Wives of men who were paid low wages, men who fished or labored for a living, often made the lace to supplement their family's income. The museum explains that making one square centimeter of lace can take up to five hours; perhaps thousands of hours were required for a lace handkerchief or collar.

Queen Victoria

Honiton lace became very popular when Queen Victoria selected it to adorn her wedding gown. However, she was not the first royal to be married in white; she was the most popular and was married in the age of photography. The tradition of white wedding gowns adorned with lace persists to this day.

Missionaries

Victorian missionary to India Samuel Mateer recorded that "Lacemaking, introduced by Mrs. Mault in her boarding school at Nagercoil... has succeeded to perfection. Admirable specimens of fine pillow lace, in cotton and gold and silver thread, manufactured at the Mission school, were shown at Madras and in the great London and Paris Exhibitions, in all of which they gained prize medals... A suggestion has recently been made that it might be more profitable, instead of merely copying and repeating, as has hitherto been done, the old standard English patterns and styles, to get up real Indian designs in accordance with the purest national taste and styles of art, to establish the Nagercoil lace as a purely indigenous production."

Self-Expression

Profitable, as he used it in the era, did not simply mean that it would make more money. It meant beneficial. It was a nod to her progressive nature that Mault encouraged the girls to adapt English methods to their native designs and tastes; they were not to be transformed into English lace-makers but taught to make lace in a manner that could express their own heritage and culture. The Maults and other missionaries networked through the British communities to ensure a healthy market for the lace goods.

Gnanadason concludes, "There are thousands of women in their homes doing lace and embroidery as a cottage industry in all the villages of Kanyakumari District and other areas of the old L.M.S. in Nagercoil, Neyyoor, Marthandam, Parasalai, Trivandrum, Attingul, and Quilon. There are established Mission Centers which give out the work, receive them, and pay the women. The proceeds of these have gone into the building of Churches, Schools, Hospitals, and Colleges, besides supporting work among women. The work offers a means to thousands of women who cannot be otherwise employed to subsidize their family income."

{Mehndi photo credit: Public Domain, Photo by Ravi Sharma on Unsplash}

{Lace photo credit: Sabine Baring-Gould – File:A book of the west; being an introduction to Devon and Cornwall.djvu, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23882306}

{Queen Victoria photo credit: Franz Xaver Winterhalter [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons}